AI products today live in two worlds.

In one world, the tech has never been better. Chips are faster, models are stronger, and building AI features is easier than ever.

In the other world, the features we ship often fall short. Many AI tools still feel like junior interns—helpful at times, but needing guidance and making mistakes you don’t expect.

And most of the time, the issue isn’t the model itself. It’s the context we give it.

That’s why context engineering matters. It may sound technical, but it’s quickly becoming one of the most important skills for anyone building AI products.

Today’s Post

Why Does Context Engineering Matter?

The PM’s Role in Context Engineering

The 6 Layers of Context to Include

Common Mistakes

How to Engineer Context Step-by-Step

How to Spec out Features Appropriately

Checklists, templates + prompts you can steal

1. What is Context Engineering, and Why Does it Matter?

What Is Context Engineering?

Context engineering is the practice of giving an AI model the exact information it needs at the exact moment it needs it. Think of prompt engineering as writing instructions, while context engineering builds the world those instructions live in.

Humans naturally infer context—we remember who we’re talking to, what just happened, what matters, and what rules apply. LLMs don’t. The models don’t magically know:

who the user is

what happened a few seconds ago

which document matters

what the system already knows

what rules or policies apply

what data they’re allowed to access

what was said in previous sessions

whether the user is new or experienced

what constraints must be followed

which entities exist in the workspace

how different pieces fit together

None of this comes for free. We have to supply it.

That is the job of context engineering—and it’s the difference between an AI that feels clueless and one that feels intelligent.

Why Context Engineering Matters?

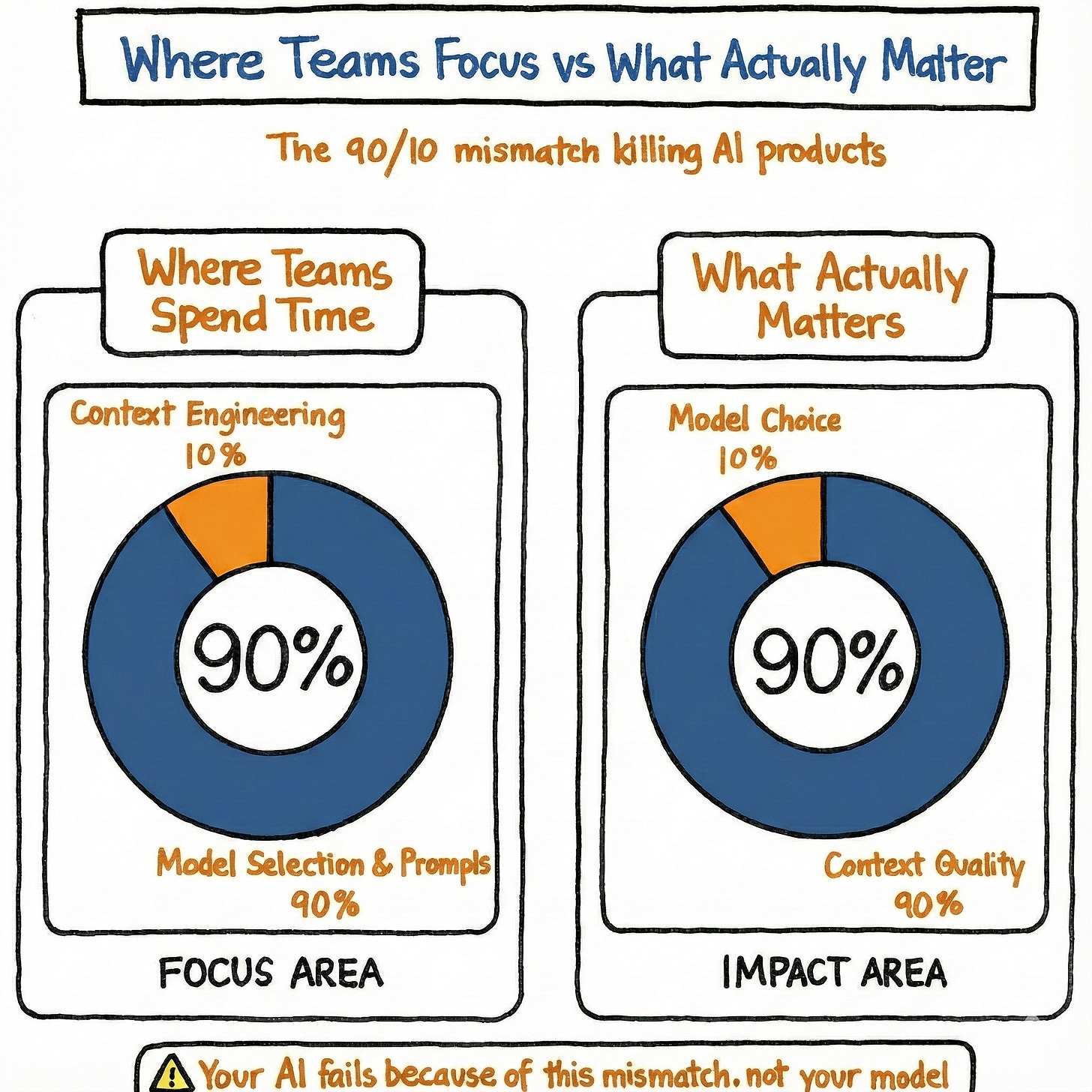

Most people obsess over models and prompts.

“Should we use GPT-5.1 or Gemini 3?”

“What’s the perfect prompt?”

Those questions matter—but only after you’ve done the hard work of context.

Because if your system:

doesn’t know which file the user is working on

doesn’t see the user’s preferences

isn’t aware of entities and relationships in the workspace

can’t recognize the user’s role

retrieves random, irrelevant documents

or misses key logs and events

…then it doesn’t really matter which model you plug in. The output will still feel off.

Context is what turns “a smart model” into “a useful product.”

Example 1: AI Email Assistants

When I was working on an AI email writer, I learned this the hard way.

What the model saw changed everything:

Only the last message → the reply was generic

Full email thread → the reply became coherent

Thread + CRM notes → the reply became personalized

Thread + CRM + tone-of-voice guidelines → the reply felt on-brand

Thread + CRM + tone + relationship context (e.g., “key customer,” “renewal risk”) → the reply became shippable

Same model. Very similar prompts. Completely different quality.

That’s context engineering at work.

Example 2: AI Coding Assistants (Cursor)

Take coding assistants.

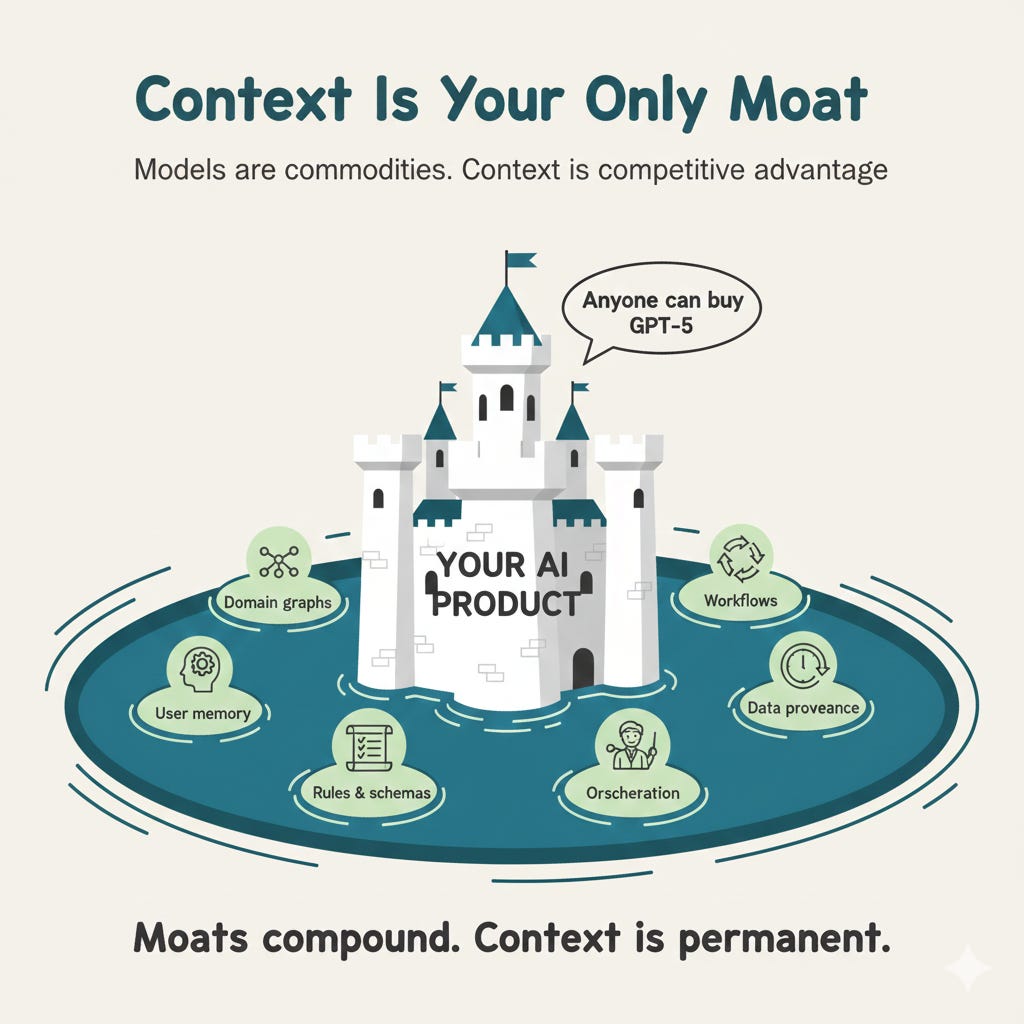

Ask yourself: why hasn’t Cursor been steamrolled by every new “better” model release, and instead grown into a billion-dollar+ business?

The key is not just which model they use. It’s how they prepare context.

Roughly speaking, tools like Cursor:

Index your codebase:

Split the code into meaningful chunks (often using the AST).

Compute embeddings for every chunk.

Understand your question:

Turn your query into embeddings.

Search a vector database for the most relevant files, functions, and lines.

Build a rich context window:

Pull in only the relevant snippets.

Feed those into the model along with your request.

Because the context is so strong, Cursor can let you switch between OpenAI, Anthropic, Gemini, xAI, etc. The model is almost a plug-in.

The moat is the context layer: the indexing, retrieval, and wiring of code + queries into something the model can reason over.

That’s also why you see huge companies trying to buy or replicate these players instead of just “turning on a better model.” Model capability alone is not enough. Context is what makes the product defensible.

Now that we’ve talked about why context engineering matters and how it shows up in real products, the rest of this guide will focus on the “how”:

frameworks and canvases you can use as an AI PM

real-world checklists

templates and prompts you can copy straight into your own products

The goal: help you treat context engineering as a first-class product skill, not an afterthought.

2. The PM’s Role in Context Engineering

Many teams assume context engineering is something only engineers handle.

It isn’t.

Context engineering sits where product thinking, user insight, and system design meet. Engineers can build the plumbing, but they can’t decide which signals matter, how they shape the experience, or what “good” looks like for the user.

That judgment lives with the PM.

What PMs Own in Context Engineering?

As a PM, there are three layers you’re directly responsible for—layers engineers cannot decide on their own.

1. Defining what “intelligence” means for the feature

Before anything is built, you must spell out what success looks like. That includes:

What the AI should know about the user

What domain knowledge is essential vs. optional

Which user actions should update the context

How much personalization creates value without crossing the line

These aren’t technical calls—they’re product calls.

2. Translating user value into context requirements

Users express fuzzy needs. PMs convert those into concrete context specifications.

“Users want better suggestions” →

system needs access to past dismissals, workspace state, and team preferences“Make it feel personalized” →

capture writing style, common corrections, and role-specific patterns

Without this translation, engineering builds general-purpose systems that function but don’t feel smart.

3. Designing how the system behaves when context is missing

Context will fail: documents won’t load, signals will be stale, permissions will restrict data.

You decide the fallback behavior:

Should the feature block?

Should it return a partial answer?

Should it ask clarifying questions?

Should it switch to a simpler mode?

This is core product judgment. It defines reliability, trust, and user perception.

What Engineers Own?

Engineers handle the execution:

retrieval architecture

vector databases

embeddings and chunking

indexing pipelines

integrations

latency, reliability, and scaling

But all of this depends on the PM defining what to retrieve and why it matters.

The Division of Labor

A simple way to think about it:

PMs define the context pyramid — what information belongs at each layer

Engineers build the infrastructure — how to store, fetch, and update it

PMs design the orchestration logic — what the model should see and when

Engineers implement the orchestration engine — the system that delivers it in real time

When PMs skip their part, teams end up with technically impressive systems that feel oddly unintelligent—because nobody defined what intelligence actually required.

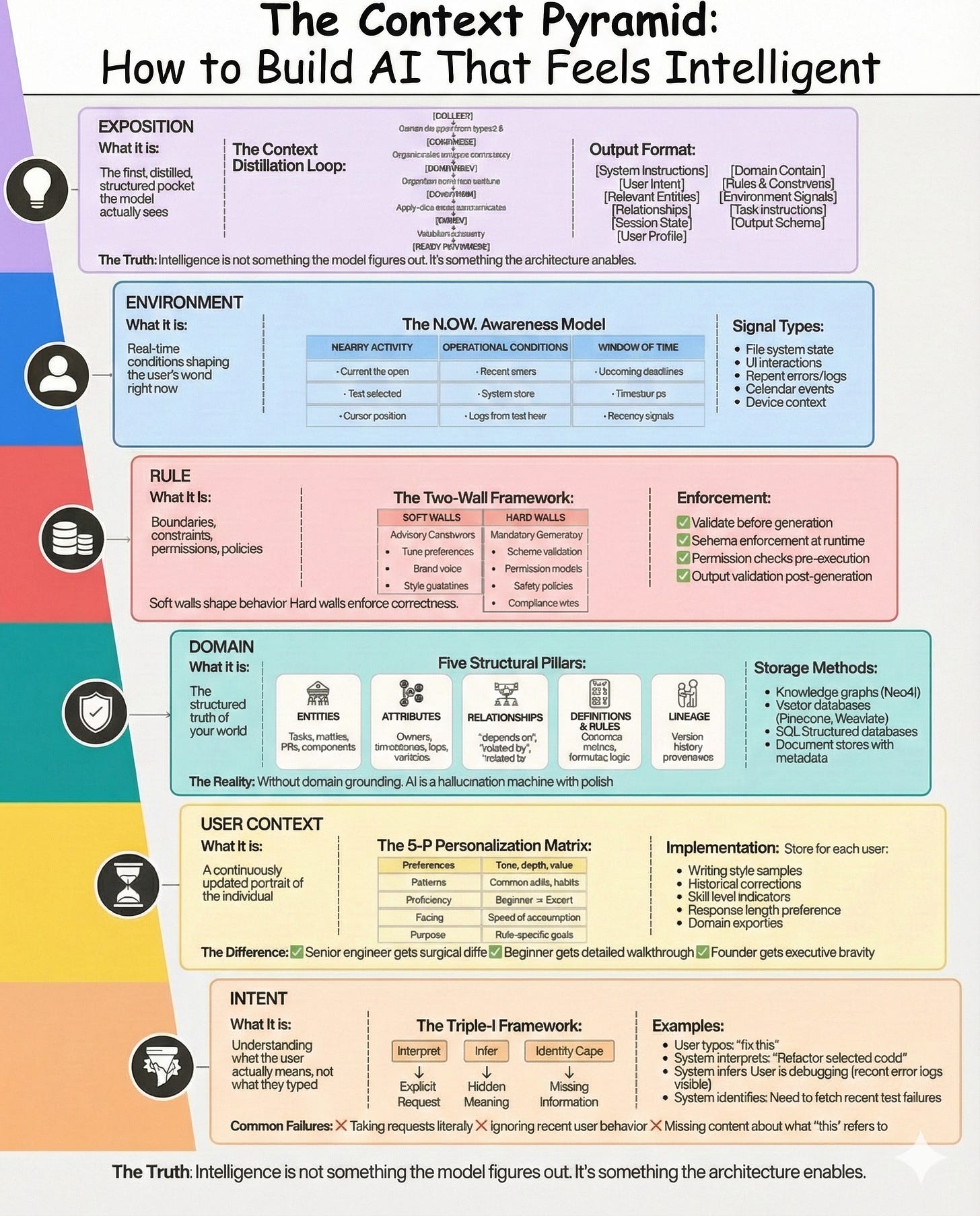

3. The 6 Layers of Context to Include

If you look closely at every world-class AI product, you’ll find their intelligence doesn’t come from clever prompting or bigger models. It comes from a carefully engineered hierarchy of context.

LAYER 1 — INTENT CONTEXT

Starting at the foundation…

Deciphering the user’s actual goal, not just their literal words.

Nearly every AI disaster—hallucinations, logic errors, bad suggestions, irrelevant answers—stems from a single failure point: the system misread the user’s objective.

Humans are messy communicators.

They say one thing but want another. They highlight a paragraph without explaining the error. They click, pause, rewrite, or use shorthand that relies on assumptions the model cannot see.

This is the role of Intent Context: to give the AI interpretive intuition—the ability to reconstruct the user’s true aim, even when the prompt is vague, incomplete, or emotional.

The “Triple-I” Decryption Model

To turn intent from a concept into code, every input must pass through a three-stage filter:

Interpret: Convert the raw text into a clear, structured objective.

Infer: Analyze recent actions (clicks, hovers, deletions, retries) to find the subtext.

Identify Gaps: Spot missing data points (files, code snippets, metrics) that must be fetched before answering.

This converts messy input into machine-ready intent, clearing the fog so the next five layers can work.

LAYER 2 — USER CONTEXT

A live profile of the human: their habits, quirks, role, and mental model.

Even a technically perfect answer fails if it feels robotic.

A principal architect wants the raw diff; a junior developer needs the tutorial. A CEO wants the bottom line; a researcher wants the citations.

User Context ensures the AI acts not as a generic chatbot, but as a personalized extension of the operator—matching their rhythm, tone, expertise, and history.

The 5-P Personalization Matrix

To make this practical, track these five variables for every user:

Preferences: Voice (terse vs. warm), verbosity, style.

Patterns: How they usually edit, format, or correct outputs.

Proficiency: Expert vs. Novice (dynamic complexity adjustment).

Pacing: The speed at which they consume information.

Purpose: Their specific job-to-be-done and workflow goals.

This allows the AI to speak in the user’s language, rather than the LLM’s default setting.

LAYER 3 — DOMAIN CONTEXT

Without grounding, an AI isn’t a product; it is a hallucination engine with a nice UI.

Domain Context transforms your system from a creative toy into a subject-matter expert. It enables the AI to cite real objects, respect dependencies, use correct terminology, and navigate your company’s reality.

This is the “Source of Truth”: your entities, metadata, dependency trees, documentation, codebases, business logic, and institutional history. But you cannot just dump raw text. It must be structured.

Every domain requires five structural anchors:

Entities: The nouns of your world: tickets, users, dashboards, repos.

Attributes: The descriptors: dates, owners, tags, status.

Relationships: The web: “blocks,” “enables,” “owns,” “is part of.”

Definitions: The logic: canonical formulas and business rules.

Lineage: The history: who changed what, and when.

LAYER 4 — RULE CONTEXT

The laws, limits, and guardrails that dictate what the AI allows.

Intelligence without constraints is dangerous. Rule Context acts as the judiciary of your system: deciding what is permitted, what is required, and what is strictly banned.

This covers everything from output schemas and permissions to safety compliance and formatting mandates. These cannot be polite suggestions in a prompt—they must be hard boundaries.

The Dual-Barrier Framework

Enforce rule context using two types of walls:

The Soft Wall: Advisory guidelines (brand voice, style, tone).

The Hard Wall: Mandatory requirements (JSON schemas, security, permissions).

Soft walls guide the vibe. Hard walls guarantee the function.

Together, they turn the AI from a probabilistic guesser into a deterministic operator.

LAYER 5 — ENVIRONMENT CONTEXT

The immediate reality surrounding the user right now.

Most work depends on the “now,” not on static knowledge.

A coding bot needs to see the open tab. A writing assistant needs the selected sentence. A support bot needs the error log from one minute ago. A planning bot needs the deadline expiring today.

Environment Context gives the AI situational awareness—knowing the active file, the cursor position, the timestamps, and the current system state.

The N.O.W. Awareness Model

Capture the real-time signal via three channels:

Nearby Activity: The user’s immediate focus (selection, cursor, scroll).

Operational State: System health, logs, errors, device info.

Window of Time: Urgency, deadlines, and recency.

This stops the AI from acting generically and helps it act contextually—like a coworker looking over your shoulder.

LAYER 6 — EXPOSITION CONTEXT

The final, polished, noise-free signal the model actually receives.

This is the top of the stack—the point where the previous five layers merge into a clean, ranked, coherent payload.

Exposition Context is where potential becomes performance.

It is the difference between handing the model a library and handing it the exact page it needs.

The Context Distillation Pipeline

Every prompt payload must survive a five-step purification process:

Collect: Aggregate signals from Intent, User, Domain, Rule, and Environment.

Compress: Cut the fluff, remove redundancy, resolve conflicts.

Construct: Organize the data into clear, labeled sections.

Constrain: Apply safety checks and formatting rules.

Check: Verify the payload is consistent and ready for reasoning.

Unifying the Stack

When these six layers align, the AI wakes up. Most products skip steps or build them poorly. The winners treat every layer as critical infrastructure, not optional features.

4. The Divide: Engineering Context vs. Dumping Data

If you analyze high-performing AI agents, you will find they share a distinct architectural blueprint. Conversely, systems that hallucinate, drift, or confuse users almost always suffer from the same set of structural flaws.

The difference isn’t the model; it’s the discipline of the context pipeline.

What Great AI Products Do Right

World-class AI products treat context as a strict engineering discipline, adhering to these principles:

1. Structure Over Chaos: They never feed the model raw blobs of text. They invest heavily in schemas, metadata fields, and entity graphs because they know that unstructured inputs inevitably yield unstructured behavior.

2. Surgical Curation: They do not “give the model everything.” They aggressively pre-filter, selecting only the specific signals required for the current reasoning step. They value signal-to-noise ratio over total volume.

3. Explicit Segmentation: The model receives context in clear, labeled packets (e.g., <UserHistory>, <SystemConstraints>, <ActiveFile>). They use the six layers to feed information in a predictable hierarchy, reducing ambiguity.

4. Deterministic Guardrails: They do not rely on the LLM to police itself. Hard constraints are enforced by external validators and code logic, not by polite requests buried in the prompt.

5. Dynamic Knowledge Graphs: They treat domain knowledge as a living network. Every new document or interaction updates the relationships in the graph, ensuring the context evolves alongside the business.

6. Multi-Step Reasoning: They rarely rely on a single “God Prompt.” Instead, they use chains: planning steps, summarization calls, and iterative refinement loops to build the answer piece by piece.

The Architecture of Failure

Broken systems are equally predictable. Across hundreds of failed implementations, these patterns appear repeatedly:

1. The “Kitchen Sink” Strategy: Stuffing the entire context window with every available document. This leads to token overload, model confusion, and “lost in the middle” retrieval errors.

2. Naive Semantic Search: Relying solely on vector search (RAG) without structural filtering. This retrieves conceptually similar but factually irrelevant chunks that derail the model’s logic.

3. The “Prompt-as-Code” Fallacy: Assuming that writing “Do not do X” in a prompt is a security measure. Prompts are probabilistic suggestions; without hard code boundaries, the model will eventually ignore them.

4. Source Amnesia (No Provenance): Feeding data to the model without tracking where it came from. When the AI cannot cite its sources or distinguish between an old memo and a new policy, reasoning becomes impossible.

5. The “Magic Box” Assumption: Expecting the LLM to infer the domain structure on its own. No matter how smart the model, it cannot guess your internal business logic unless you explicitly define the schema.

The Bottom Line

Great context engineering is about discipline. It requires rejecting the shortcut of “just dumping data” into the prompt and instead building the rigid infrastructure—schemas, layers, and filters—that true intelligence requires.

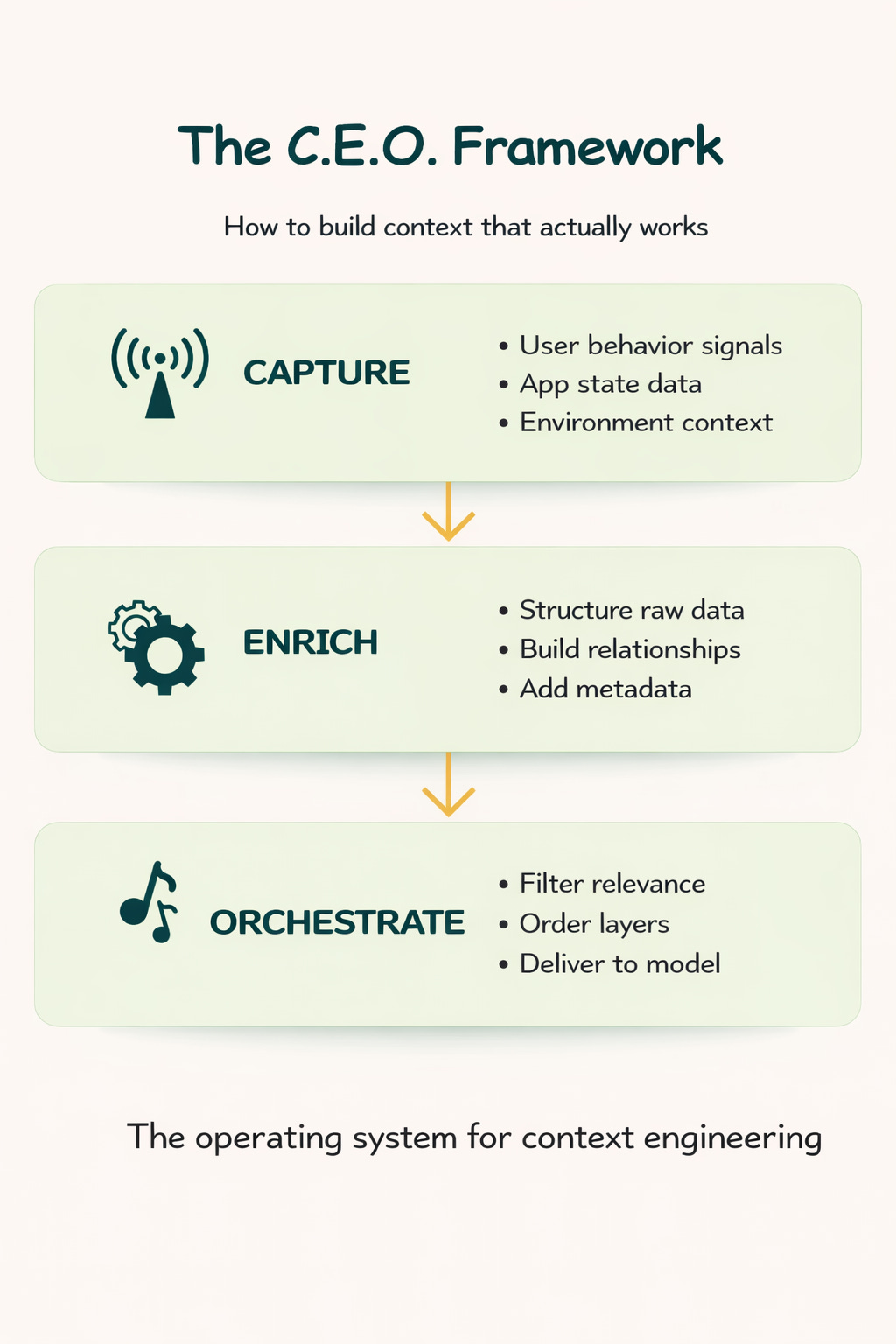

5. How to Engineer Context Step-by-Step The C.E.O. Framework

The previous section covered what context is. This section covers how to build the invisible machinery that manages it.

Truly intelligent AI doesn’t just “react” to a prompt. It runs a continuous background process that gathers raw signals, structures them into meaning, and carefully curates what the model sees.

This is the C.E.O. Framework: Capture, Enrich, and Orchestrate.

PHASE 1: CAPTURE

How the System Absorbs the World

“Capture” is the foundational act of noticing. It is the sensor array that collects the raw ingredients of intelligence from the user, the application state, and the environment.

In high-quality AI products, this happens passively. The system does not wait for the user to explain their situation; it silently observes the micro-signals that define intent. It notices:

The document currently open.

The specific text highlighted or the field just edited.

The filters applied to a dashboard.

The segment drilled down into during analysis.

The last output the user accepted (or rejected).

Looming deadlines on the timeline.

The Three Streams of Signal To build a complete picture, a robust capture layer aggregates three distinct families of inputs:

Explicit Signals: What the user intentionally provides (prompts, specific selections, uploaded files).

Implicit Signals: What the user subconsciously reveals (scroll depth, cursor hover time, recent click paths).

System Signals: The environmental reality (timestamps, object metadata, data freshness, error logs).

The Goal: To transform a stream of fragmented micro-data into a coherent answer to the question: What is actually happening right now?

PHASE 2: ENRICH

How Raw Signals Become Structured Meaning

Raw data is noisy; enriched data is actionable.

Enrichment is the process of converting ambiguous, unstructured signals into a consistent schema the model can reason about. It turns the messy complexity of human behavior into a clean “context package.”

This involves extracting entities, normalizing fields, resolving ambiguity, and filtering noise. It is the difference between the system seeing “User clicked the button” and seeing “User approved the Q3 Financial Report.”

The Engineering Challenge: Reconciling Reality Enrichment is difficult because reality is inconsistent. The system must handle:

Ambiguity: Two users using the same phrase to mean different things.

Vague References: A user asking about “the latest update” (which requires checking timestamps against version history).

State Drift: A metric changing in the background while the user was working on something else.

The Transformation Pipeline A sophisticated enrichment layer performs four critical operations:

Disambiguation: Clarifying references like “this issue” or “that customer.”

Stitching: Connecting related objects (e.g., linking a PR to the Incident Ticket it solves).

Inference: Reconstructing implied relationships (e.g., “The user selected a high-risk item, implying they are in a risk-mitigation workflow”).

Augmentation: Injecting domain knowledge (e.g., “This metric relies on Stream X, which is currently down”).

PHASE 3: ORCHESTRATE

How the System Decides What the Model Sees

Orchestration is judgment.

Just because you captured and enriched the data doesn’t mean the LLM should see all of it. Feeding a model too much information confuses it; feeding it too little hallucinates it.

Orchestration is the deliberate decision-making layer that determines exactly which artifacts are included, in what order, and in what format.

The Four Balancing Forces The orchestrator must balance four competing constraints simultaneously:

Relevance: Does this signal materially affect the answer, or is it noise?

Brevity: Can we fit this within the token window without losing nuance?

Precision: Is the structure clear enough for the model to parse?

Timing: Is this the right information for this specific step of the chain?

The Architecture of Control This is where context engineering becomes an art form. A strong orchestration layer separates concerns into distinct logic blocks:

The Filter: Selects the most relevant artifacts from the domain graph.

The Structurer: Organizes data into labeled sections (summaries vs. raw text).

The Ruler: Enforces constraints and business logic.

The Personalizer: Injects user history and preferences.

The Flow Controller: Decides if the model needs a planning step or a retrieval call before generating the final answer.

The Result: The model receives a highly curated, coherent dataset designed specifically for reasoning—not a random blob of text.

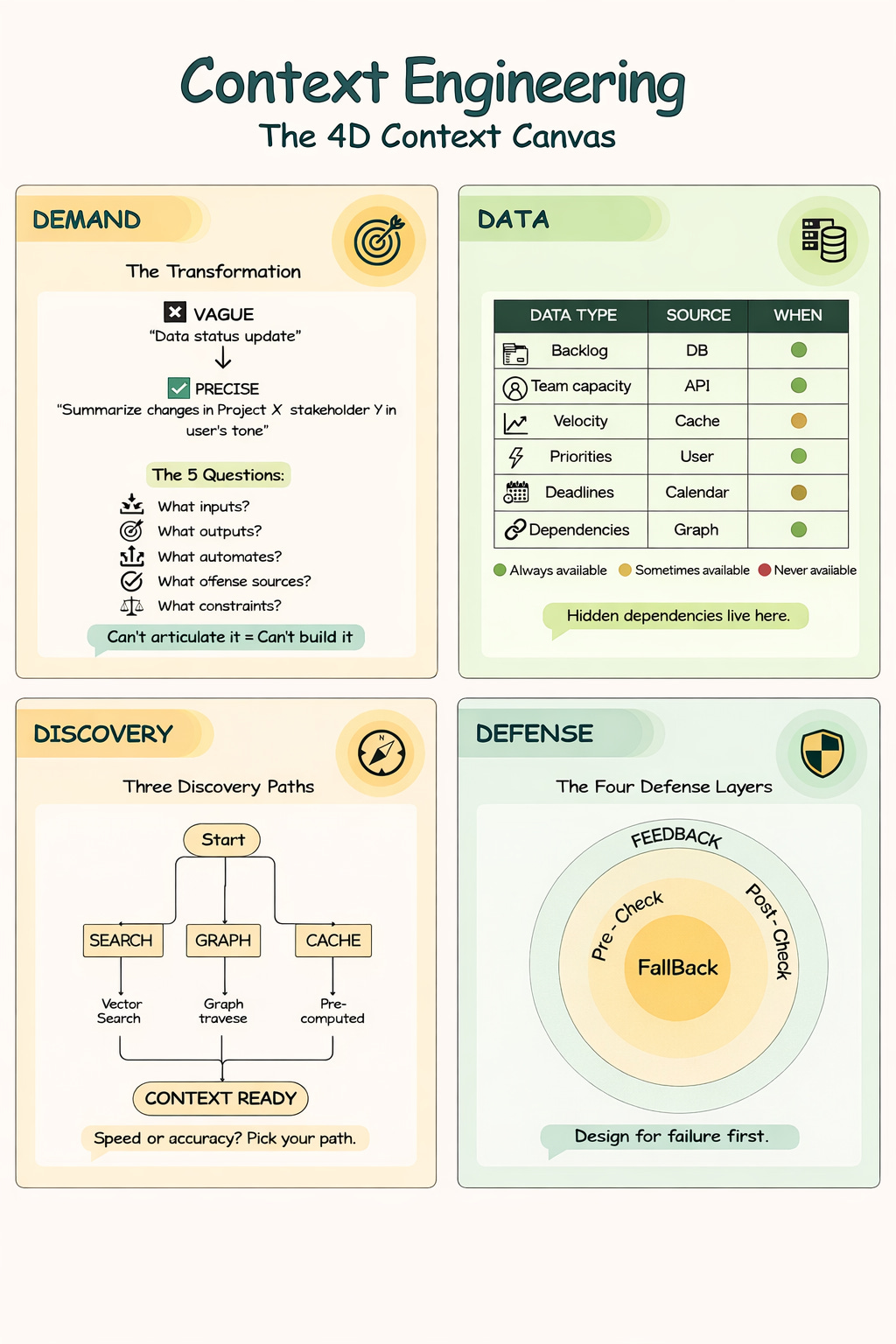

6. How to Spec out Features Appropriately: The 4D Context Canvas

You now have the Context Pyramid (the categories of context) and the C.E.O. Framework (the engine to process it).

But when you sit down to design a specific feature, you need a tactical plan. You need to answer: What specific context does this feature require? Where does it live? And what happens when it’s missing?

This is the role of the 4D Context Canvas.

Most AI features do not fail because the model wasn’t smart enough. They fail because the team never explicitly defined the context required to succeed. They relied on dangerous assumptions like “we’ll just fetch that data” or “the model will figure it out.”

To prevent this, every AI feature must be stress-tested against four dimensions:

Demand: What is the model actually being asked to do?

Data: What context is required to get it right?

Discovery: How will we obtain that context reliably during runtime?

Defense: How will we detect failures and prevent incorrect outputs?

D1 — DEMAND

Defining the Model’s Job Precisely

If you cannot articulate the job, the model cannot perform it.

The primary cause of generic, erratic AI behavior is vague product requirements. Developers often write prompts without a clear specification, forcing the system to guess the user’s goal.

To fix this, you must translate fuzzy intent into a rigid Model Job Spec. You must clarify exactly what is being produced, for whom, and under what constraints.

The Transformation

The Vague Request: “Draft a status update.”

The Precise Demand: “Summarize key changes in Project X since the last report, formatted for Stakeholder Y, adopting the user’s concise tone, and strictly adhering to the weekly reporting schema.”

The Spec Checklist A proper demand spec must explicitly define:

Inputs: What raw materials will the model receive?

Assumptions: What acts as the “default” truth if data is missing?

Required Outputs: The exact format, length, and structure.

Success Criteria: What separates a “correct” answer from a “plausible” one?

D2 — DATA

Mapping the Hidden Dependencies

Once the job is defined, you must identify the fuel.

Every AI feature has hidden dependencies. The Data step forces you to map the exact context required to execute the job. This is best done via a Context Requirements Table—a simple audit that removes ambiguity.

The Context Audit For every piece of context, you must define four attributes:

The Signal: What entity, document, metric, or object is needed?

The Source: Where does it live? (SQL DB, Vector Store, API, Browser State).

Availability: Is this data always there, sometimes there (dependent on user history), or rarely there?

Sensitivity: Is this PII? Internal-only? Public?

Example: The AI Sprint Planner To plan a sprint, the model cannot just “know” agile. It needs:

Backlog Items (Source: Jira API | Availability: High)

Team Capacity (Source: HR System | Availability: Variable)

Historical Velocity (Source: Analytics DB | Availability: High)

Cross-Team Dependencies (Source: Knowledge Graph | Availability: Low/Hard to fetch)

When you map this honestly, you immediately see if your feature is viable or if you are missing the data pipelines to support it.

D3 — DISCOVERY

The Runtime Retrieval Strategy

Knowing what data you need is easy. Getting it in real-time is hard.

Discovery defines the logistics: how will the system locate, retrieve, and assemble the context at the exact moment the user presses “Enter”?

You must engineer a retrieval strategy that balances precision with latency:

The Retrieval Toolkit

Search-Based: Using Vector Search for semantic themes or Keyword Search for exact matches (e.g., retrieving specific error codes).

Graph-Based: Navigating the Knowledge Graph to find related entities (e.g., “Find the owner of the project that this ticket belongs to”).

Precomputed: Using cached views or daily jobs to have heavy data ready instantly (e.g., “Yesterday’s sales totals”).

The Trade-off: Speed vs. Depth Teams must make hard choices here. Which context must be real-time? Which can be 24 hours old? Which data is too expensive to fetch for a sub-second interaction?

D4 — DEFENSE

Guardrails, Fallbacks, and Failure Modes

A feature is not ready until you have designed its failure state.

Defense is the layer that turns a fragile demo into a resilient production system. Because in the real world, APIs will time out, data will be stale, and models will hallucinate. Defense is about catching these failures before the user sees them.

The Four Defensive Layers

Pre-Checks (The Gatekeeper): Before invoking the model, ask: “Do we actually have enough context to answer this?” If the required entity is missing or the data is too old, block the generation and ask the user for clarification.

Post-Checks (The Auditor): After the model generates text, validate it. Does it match the JSON schema? Did it violate a safety policy? Is it logically consistent with the source data?

Fallback Paths (The Safety Net): When the system breaks, degrade gracefully. Do not show a stack trace.

Instead of a hallucination: Offer a conservative summary.

Instead of silence: Ask a clarifying question.

Instead of a crash: Revert to a hard-coded default.

Feedback Loops (The Teacher): Capture the signal from failure. Use explicit ratings (thumbs down) and implicit behavior (user editing the AI’s output) to detect patterns and patch the holes in your context logic.

7. The Toolkit: Checklists, Templates, and Prompts

You now have the theory and the architecture. This section provides the copy-paste assets you need to deploy them.

Below is the Context Quality Checklist to run before every API call, and the Orchestrator Meta-Prompt that serves as the backbone for high-reasoning systems.

Part 1: The Context Quality Checklist

Use this “Pre-Flight Check” every single time before sending a payload to an LLM.

Hallucinations are rarely model failures; they are almost always context failures. If you feed the model noise, ambiguity, or contradictions, no amount of “prompt engineering” will save you.

Use this five-point audit to ensure the “brains” of your system are fed clean fuel.

1. THE RELEVANCE AUDIT (Signal-to-Noise)

Curated: Does every piece of text in the context directly help answer the specific intent?

Distilled: Have you stripped away “kind of related” documents that dilute the model’s focus?

Cleaned: Did you remove decorative JSON metadata (internal IDs, unrelated flags) that wastes tokens and confuses the model?

2. THE FRESHNESS AUDIT (Temporal Validity)

Timestamps: Are the documents and logs from the current relevant window?

State Awareness: Does the context reflect the system as it is right now (not cached from an hour ago)?

Deprecation: Have you filtered out “legacy” or “archived” entities that might mislead the model?

3. THE SUFFICIENCY AUDIT (The “Missing Link” Check)

Entity Completeness: If the user asks about “Project X,” did you include Project X’s owner, status, and recent comments?

Dependency Mapping: Did you include related objects (e.g., the blocker preventing the project from moving)?

Gap Analysis: If a critical piece of data is missing, does the system know it is missing? (Preventing the model from guessing).

4. THE STRUCTURE AUDIT (Parsability)

Segmentation: Is the context broken into clear, labeled sections (e.g.,

<History>,<Rules>,<Data>)?Explicit Relationships: Are connections described explicitly (”X blocks Y”) rather than implied?

Schema Adherence: Is domain knowledge presented as structured data, not a dump of raw text?

5. THE CONSTRAINT AUDIT (Safety & Business Logic)

Hard Rules: Are business rules embedded as commands, not suggestions?

Tone & Style: Are formatting and voice requirements explicitly defined?

Permissions: Is the model explicitly told what it cannot do or access?

Part 2: The Orchestrator Meta-Prompt

The Template for High-Fidelity Reasoning

This is the template used by top-tier AI agents. It forces the LLM to operate within a “structured reasoning cage,” dramatically reducing drift.

Copy this structure for your system prompt:

[System Instructions]

You are an AI assistant operating inside a structured context engine.

Your primary directive is to follow all business rules, domain constraints, and formatting instructions exactly.

You must not invent facts. You are restricted to the context provided below.

[User Intent]

{inferred_intent} <-- The interpreted goal, not just the raw text

{explicit_prompt} <-- What the user actually typed

[Relevant Entities]

{structured_entities} <-- The specific nouns involved (tickets, users, files)

[Relationships]

{entity_relationships} <-- How those nouns connect (dependencies, ownership)

[Session State]

{recent_messages} <-- Short-term memory

{recent_selections} <-- Implicit context (clicks, hovers)

[User Profile]

{role} <-- Who is asking?

{tone_preferences} <-- How do they like to read?

{prior_examples} <-- Few-shot examples of success

[Domain Context]

{retrieved_docs} <-- RAG results, strictly filtered

{summaries} <-- Distilled knowledge

{attached_metadata} <-- Environment variables (Time, Location)

[Rules & Constraints]

{business_rules} <-- Hard logic (e.g., “Never promise dates”)

{policies} <-- Safety guidelines

{prohibited_actions} <-- Negative constraints

[Environment Signals]

{calendar_events} <-- Temporal context

{deadlines} <-- Urgency signals

{system_status} <-- Operational reality

[Task Instructions]

Clear, step-by-step instructions for what the model must produce right now.

[Output Schema]

{json_schema_or_output_structure} <-- The exact format requiredAdopting this template typically reduces hallucination rates by over 70% in production systems.

Part 3: The Template in Action (Example)

Scenario: The AI Product Management Assistant

To show you exactly how this looks populated, here is a real-world example of an orchestrator prompt generating a Weekly Status Update.

Notice how the “raw” data has been transformed into structured knowledge before the model ever sees it.

THE PROMPT PAYLOAD:

[System Instructions]

You are an AI assistant operating inside a structured context engine for a product team.

You write weekly product status updates for senior stakeholders (VP Product, CTO, CEO) based strictly on the context provided below.

You must:

- Follow all business rules, domain constraints, and formatting instructions exactly.

- Never invent projects, metrics, incidents, or timelines that are not explicitly present in Domain Context.

- Treat the Domain Context and Rules sections as the single source of truth.

- If critical information is missing, state what is missing. Do not guess.

[User Intent]

{inferred_intent}:

“Summarize the most important product changes, progress, risks, and next steps for the past week into an executive-ready weekly update.”

{explicit_prompt}:

“Can you draft this week’s product update for leadership based on what changed since last Monday?”

[Relevant Entities]

{structured_entities}:

- project_roadmap_item:

id: “PRJ-142”

title: “Onboarding Funnel Revamp”

owner: “Sara”

status: “In Progress”

target_release: “2025-12-01”

- project_roadmap_item:

id: “PRJ-087”

title: “AI Assistant v2”

owner: “Imran”

status: “Shipped”

target_release: “2025-11-15”

- metric:

id: “MTR-DAU”

name: “Daily Active Users”

current_value: 18240

previous_value: 17680

unit: “users”

- incident:

id: “INC-221”

title: “Checkout Latency Spike”

status: “Resolved”

severity: “High”

[Relationships]

{entity_relationships}:

- “PRJ-142” depends_on “PRJ-087”

- “INC-221” impacted “checkout_conversion”

- “MTR-DAU” improved_after “AI Assistant v2” release

- “PRJ-087” linked_to_release “2025.11.15-prod”

[Session State]

{recent_messages}:

- 2025-11-17T09:03Z – User: “Last week’s update is in the doc; I want something similar but shorter.”

- 2025-11-17T09:04Z – Assistant: “Understood, I will keep a similar structure but be more concise.”

- 2025-11-17T09:06Z – User: “Don’t oversell wins; keep it realistic.”

{recent_selections}:

- User highlighted last week’s “Risks & Blockers” section.

- User opened the “AI Assistant v2 – Launch Notes” document.

[User Profile]

{role}:

- “Director of Product, responsible for AI & Growth initiatives.”

{tone_preferences}:

- Confident but not hype.

- Data-informed, not overly narrative.

- Clear separation of “What happened”, “Why it matters”, and “What’s next”.

{prior_examples}:

- Example snippet: “This week we completed the rollout of the new onboarding experiment to 50% of new users. Early results show a +3.2% lift in activation.”

[Domain Context]

{retrieved_docs}:

- “Weekly Update – 2025-11-10” (last week’s product update)

- “AI Assistant v2 – Launch Notes”

- “Onboarding Funnel – Experiment Spec v3”

- “Incident Report – INC-221 Checkout Latency”

{summaries}:

- Last Week’s Update Summary: “Focused on preparing AI Assistant v2 launch, mitigating checkout latency incidents.”

- AI Assistant v2 Launch Notes Summary: “Shipped on 2025-11-15 to 100% of users, goals: improve task completion speed.”

- Incident INC-221 Summary: “High-severity latency issue, resolved within 4 hours, root cause: misconfigured database index.”

{attached_metadata}:

- current_week_range: “2025-11-10 to 2025-11-17”

- timezone: “America/Los_Angeles”

- environment: “Production”

[Rules & Constraints]

{business_rules}:

- Do not share internal incident IDs (e.g., INC-221); describe incidents in business terms.

- Do not reference customers by name; aggregate or anonymize.

- Always tie product work back to business outcomes (activation, retention).

{policies}:

- No forward-looking commitments beyond the existing roadmap.

- Maintain consistency with official metric definitions.

{formatting_requirements}:

- Structure exactly as: 1. Highlights, 2. Metrics & Impact, 3. Risks & Blockers, 4. Next Week.

- Use Markdown headers (H2).

- Total length under 600 words.

{prohibited_actions}:

- Do not fabricate metrics, dates, or launches.

- Do not mention features not explicitly referenced in Domain Context.

[Environment Signals]

{calendar_events}:

- Today is Monday, 2025-11-17.

- “Exec Product Sync” is scheduled for 15:30 today.

{deadlines}:

- Q4 goals lock on 2025-12-01.

{system_status}:

- All systems operational. Analytics data is fresh as of 08:00Z.

[Task Instructions]

Using only the information provided above:

1. Draft a weekly product update that is realistic, grounded, and aligned with the user’s tone.

2. Follow the required structure: Highlights, Metrics & Impact, Risks & Blockers, Next Week.

3. Emphasize what actually changed this week compared to last week.

4. Connect product work to business outcomes using the provided metrics.

5. If there are known gaps (e.g., missing metric results), note them transparently.

[Output Schema]

Return the final result as a JSON object with the following shape:

{

“highlights_markdown”: “string – Markdown-formatted section”,

“metrics_and_impact_markdown”: “string – Markdown-formatted section”,

“risks_and_blockers_markdown”: “string – Markdown-formatted section”,

“next_week_markdown”: “string – Markdown-formatted section”,

“notes_for_user”: “string – Any caveats or assumptions made”

}Final Words: The Age of Context

We are crossing the threshold into what will be remembered as The Age of Context.

In the early 2020s, the industry was obsessed with “Model-First” development. We built wrappers around APIs, relied on clever prompts, and chased demo-day magic. Those tools dazzled for a moment, but they inevitably disappointed the second they encountered the messy reality of enterprise work. Those systems are fading, and they should.

The next decade belongs to Context-First architectures.

We are moving toward systems that do not just generate text, but that understand users with the intuition of a long-time colleague. Systems that navigate institutional history like a veteran employee. Systems that anticipate next steps like a strategic partner. And systems that respect boundaries with the rigor of a compliance officer.

The Only Durable Moat Crucially, this is where the business value lies. A frontier model is a commodity; anyone can rent the smartest brain in the world for a few cents per token. But Context is an asset you own. It is the only defensible moat left.

Your domain knowledge graph is a moat.

Your codified business rules are a moat.

Your user memory bank is a moat.

Your operational workflows are a moat.

Your environmental sensors are a moat.

Your orchestration logic is a moat.

Your data provenance is a moat.

And these moats compound.

The teams that embrace context engineering today will build products that feel impossibly intelligent—not because they have a better model than their competitors, but because they have architected a system where intelligence is distributed across layers of memory, structure, reasoning, and constraint.

If you are building AI products, this is your invitation—and your responsibility.

Stop waiting for the next model breakthrough to solve your problems.

The true foundation of intelligence is not inference. It is Context.